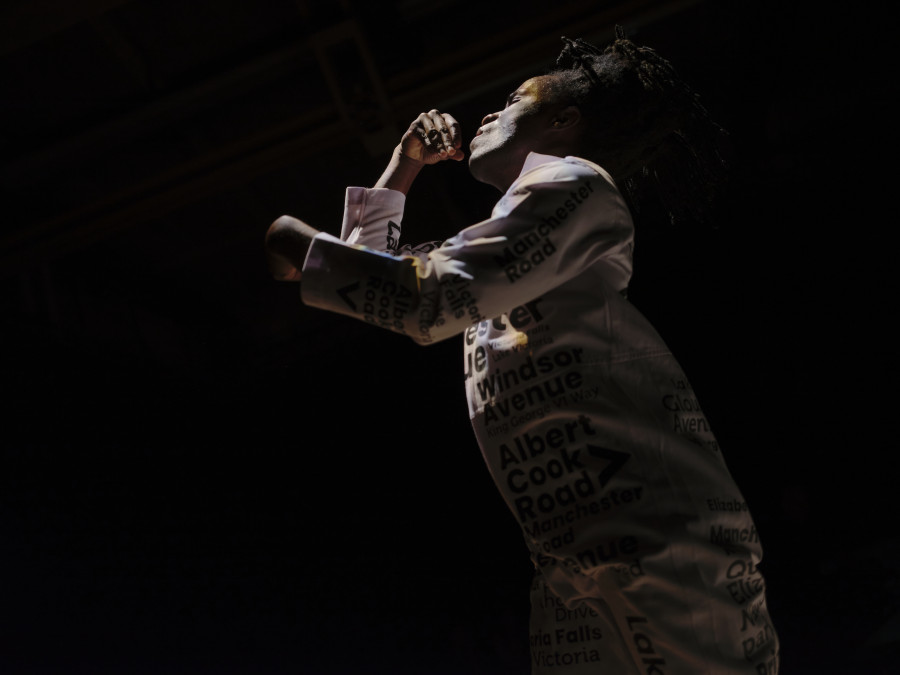

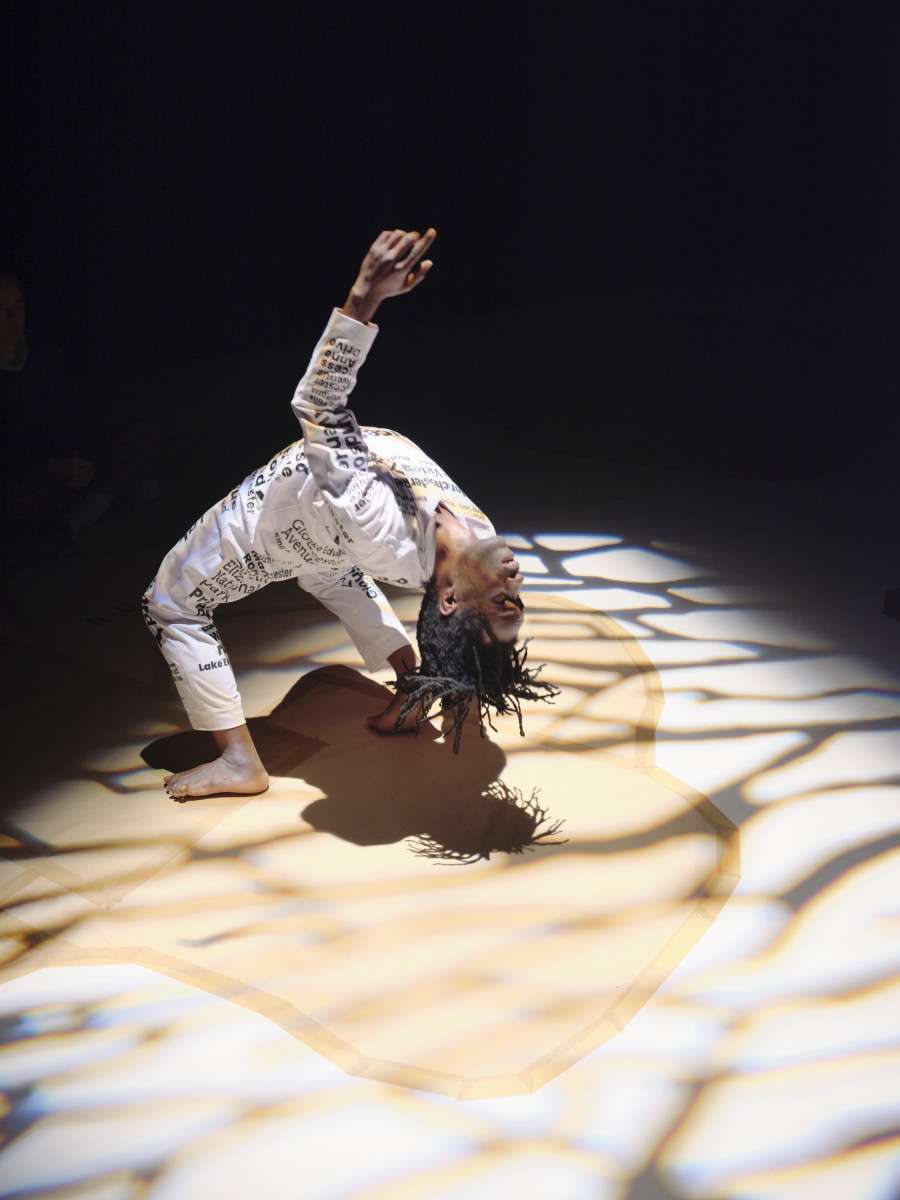

Alienation III

Robert Ssempijja (Kampala)

Luganda | with English surtitles | ages 12 and up

As a star architect of 20th-century Germany, Ernst May designed, among other things, the urban planning program ‘Neues Frankfurt’ in Frankfurt am Main, the districts of Neu-Altona in Hamburg and Neue Vahr in Bremen, as well as housing projects in the Soviet Union. From a European perspective, he created social architecture inspired by the garden city model, which was intended to bring all areas of life together in one unit. But he also realized his visions on behalf of the British administration in Kampala, the capital of Uganda. The city where Robert Ssempijja grew up, and the emerging artist’s view of May is devastating. In his performance ALIENATION III, Ssempijja, who lives in both Europe and Africa, reflects an urbanistically colonized population’s attitude to life in his choreography, because for him, architecture also includes ‘how we behave around buildings’. Until today, May's scheme for a ring-shaped new Kampala is perceived in Uganda as both a kind of fortress and a foreign body: While locals have to turn back at the gates, colonial rulers enjoy themselves inside, walking on streets named after their own heroes. Even in these times of decolonization, the choreographer, researcher and Pina Bausch fellow still feels like a stranger in his own city. Symbolically, he places street signs on stage whose names represent colonial history and connect the performance with the film ALIENATION I, which was created as an independent work. Also constantly present is the red earth of the region, which Ssempijja washes out of his hair every day. Mealy dust as his only home?

Biographies

Robert Ssempijja is an Ugandan contemporary artist, dance and researcher. He is forging a career in both formal and informal settings. Ssempijjas practice is marked by both the post-colonial era and decolonization.

Showcasing work in both traditional and non-traditional spaces, he reflects a commitment to challenging conventional norms and he is ready to embrace diverse perspectives.Ssempijja’s work consists of research projects that manifest in texts, dance films, installations and performances. He seeks to cultivate "a regenerative art practice" that transcends exploitative relationships, bridging the distorted past with the digital present. He is interested in trying out new ways to create knowledge, exploring fresh methods for organizing information and thinking up innovative structures.

Öz Kaveller was born in Istanbul and lives in Berlin. From 1984 to 1992, she studied opera chorus and clarinet at the Istanbul State Conservatory. Between 1986 and 1989, she trained in theatre acting at the Exprement Stage in Kadıköy, followed by vocal technique studies with Rafael Ortiz from 1996 to 1999, and contemporary composition with Carlo Domeniconi from 1997 to 2001.

Since 1986, she has worked across a range of disciplines including film dubbing, radio programming, choral and solo performance, as well as television acting. She currently works as a composer and sound designer for various theatres and occasionally leads workshops in choir, voice, folk dance, and performance.

She has collaborated with institutions such as GRIPS Theater Berlin, TAK Theater Berlin, Deutsches Schauspielhaus Hamburg, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Werkstatt Theater Hannover, the Lauratibor protest art collective, Laak Theater in The Hague (Netherlands), as well as Music Design, Performanz, and the National Theatre Kampala in Uganda.

Essay by Robert Ssempijja: STRUCTURE IS MAGIC

Structure is magic. Architecture, policy and design.

Excerpts from an essay by Ssempijja Robert commissioned by Moving across Threshold’ in 2022 and residence support from Camargo Foundation:

Nakulabye-Kiyayye is a magical place seen through the brown eyes of a six-year-old child. Kiyayye was the street I spent most of my childhood. It’s where my feet grew rough and my knuckles grew tough. Every minute of every hour and every hour of every day we, the children of this street, raised each other. We formed our friendships, we fought our battles and we did what we had to survive. When a big person, a grown up, interfered it was like they did not understand our world. The big person would just beat us up, they didn’t listen to who did what or why. Life was never easy but you grew accustomed to it. This paved the way for what to expect of life. We lived with the belief that we could create our own rules In life and that we, the young generation, were the future. A loose translation of Kiyayye would be ‘a place where delin delinquents reside’. Seen through the eyes of an adult, most people would consider it to be a slum where poverty is so widespread that it has become the norm, until you step outside. I remember thinking that our neighbors were rich because they could afford to eat three times a day on most days. I always wondered when they were going to start sharing their wealth with us. If you ever visit, you will find Kiyayye in the valley at the foot of Namirembe hill in the main capital of the small landlocked east African country - Uganda. The capital is called Kampala andI’ve always considered it to be my home, without questioning how the structures of the city actually affect the people who live and die there. I didn’t start questioning my home until the Covid pandemic hit in 2019. It’s a bustling city built on seven primary hills, with movement at its core. The people here always have to move to survive. If you sit too long, you’ll miss your opportunity and for many that means no food or sleep that day. The traffic never moves but the cars do. You have to be vigilant when you walk so that the cars don’t hit you when they use the pavement to try to reach their destination. The recently installed traffic lights are taken more as a recommendation whenever they actually have power to work. […] About six kilometers away there is a place called Kololo Hill which is the opposite towhere I grew up. It is situated on one of the seven hills surrounding Kampala’s city center. I can access most of the things on that hill today, but I have come to understand that this access isn’t given to everyone born in the city.

[…]

I came to learn that Kampala was designed in 1933 by Ernst May. After being repeatedly thwarted in ambitious planning work in Silesia (1919-25), Frankfurt (1925-30) and the Soviet Union (1930-33), the German modernist planner surprised even his closest friends when he announced that he would “withdraw to the African bush in order to think about it [all] in peace”. The transition from his grand European and Soviet projects to a colonial hierarchical mindset came quickly. May regarded the African landscape as a tabula rasa, where “there was no trace of visible human civilization”. He worked with great passion and energy to develop a productive and self-sufficient farmscape ‘from nothing’, complete with a small village and infrastructure for his many ‘primitive’ farmhands. He wrote condescendingly that both the Indian and the African workers, “which are here at our service [...] often need to be taught even the most elemental tasks”. May saw little irony in the fact that after being forced to abandon his work in the Soviet Union because critics had attacked his planning methods as overly bourgeois and ‘Western’, he was unable to return to his native Germany because Nazis had condemned his architecture in Frankfurt as ‘primitive’, ‘un-German’ and ‘Bolshevik’. Nazi racial purity laws had also attacked May’s Jewish family background. Taking advantage of Kampala’s hills, May designed the structure of the city. He was inspired by a model called ‘the garden city’ where each hill had its own center surrounded by agricultural land. The name Ernst roughly translates to the English meaning for ‘something which is serious’. If you look at his designs, he was a serious person and this is evident in the fact that his design implies who gets what, when and how. Kololo was designed to be an affluent neighborhood and still is. The roads lead out from the city like sun rays.

[…]

I have been in Kololo numerous times, to visit, eat and perform. But I do not understand why my performances are always shown here and not in other places within Kampala. My peers from Kiyayye never come to attend my shows. I came to realize that there are only a few people in Kampala who are privileged enough to have the time, finances and space in their minds to appreciate art. When you’re hungry you don’t have any of these things to spare.

Here you find the complete essay by Robert Ssempijja entitled STRUCTURE IS MAGIC

Credits

Concept + Performance Robert Ssempijja Music + Sound Design Öz Kaveller Dramaturgy Gert-Jan Stam Outside Eye Christoph Winkler, Israel Akpan Sunday Video Editing Larissa Potapov Costume Kazibwe Nelson Production Manager Niklaus Bein Artistic Collaboration Joseph Julius Kasozi Sound Recording Okiria Michael

Production K3 | Tanzplan Hamburg

Creation K3 | Tanzplan Hamburg, Kampnagel, 20 March 2025

Main Supporters

euro-scene leipzig is institutionally supported by the City of Leipzig and the Saxon State Ministry for Higher Education, Culture and Tourism. Co-financed by tax revenue on the basis of the budget approved by the Saxon State Parliament.